What Nature Teaches Us About Love (and What Doesn’t Appear In The Movies)

We learn to love through violent movies and bombastic songs. What if the lessons weren’t there, but on the ground?

Vanesa lives in a dollhouse, in a popular neighborhood on a noisy island. But all the hustle and bustle, the swaying of tourists, the frenetic pace, everything stays at the door.

Vanesa’s house seems off the hook of time, captured in a bubble where everything happens differently. At the back of the house, a piece of earth rescued from the asphalt emerges as a garden.

An orchard garden, a jungle garden, extremely alive. When someone asks Vanesa how she does it, she smiles, adjusts her red hair bow and answers, from the side: “with love. In this house we take care of everything with love ”.

The love that Vanesa refers to is based on respect for the primordial nature of each one, what Islamic philosophy calls the “fitra” and that classical Greek philosophy includes as “essence”. It is not a conception of a castrating and immobilizing essence, but quite the opposite: flowers are not obliged to bloom to be flowers, but rather it is by flourishing that they become.

This way of relating to the environment is the traditional way in which the original communities of the world have related to the land.

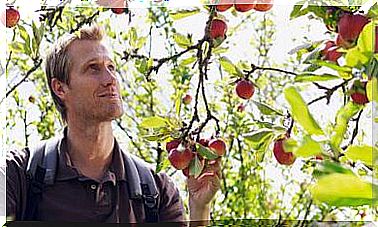

We speak, for example, of the way in which Quechuas and Aymara have a permanent dialogue with Pachamama, something that in the industrialized world we have tried to recover from the 1970s with concepts such as permaculture. This term was born in Australia in the 1970s by the hand of Bill Morrison and David Holmgreen who denounce food production that depletes the soil and reduces biodiversity.

Learn to love from the ground

This relationship with the earth and the environment can be applied to our entire way of inhabiting the world. From the garden to the couple, through our neighborhood relationships and our position in the face of the great conflicts that shake the world and of which we are also part, actively or passively.

To be able to cultivate gardens in a world full of noise, slowness is necessary. Finding ways to stop the rhythm, to breathe again, to shut up and listen again, to stop producing, to run, to remember why we were running, and to decide if we want to keep running.

The infinite flight, the constant frenzy is not a solely personal decision: we live in a world that imposes these rhythms, how can we change our rhythms if it is something so much greater than ourselves?

Let’s go back to Vanessa’s garden for a moment. It is a square of land gained from asphalt, a place without many possibilities that, however, has known how to adapt through synergies and cooperation. The land is not particularly fertile, the patio orientation is not ideal, but Vanesa has been combining plants that do well with each other, whose roots know how to distribute themselves fairly for all, with that justice that arises from living together, from the ethics of care.

The land, like love and bonds, does not admit haste: the harvest comes when it is time, it cannot be imposed or forced, at the risk of turning it into something artificial.

If we do not let everything take its time, we will achieve something that is successful in the short term, but unsustainable as a whole. Slowness gives the necessary space for observation: what does the earth need? What do plants need? What do they need from me, and what do I need from them? And also, with these questions, awareness of limits.

Permaculture dismantles the imaginary of the almighty gardener who can push the limits of the environment at will. The earth is a companion, not a productive and replaceable machine.

Hierarchy no longer works: here we are talking about the welfare of the whole. So what are the limits of the earth, and what are my own limits, as a gardener? How much time can i dedicate to it? How much care? In what way and in which way not?

The rhythm of flowers and love

Knowing one’s own possibilities and being consistent with them is a form of care and self-care, of commitment to the whole based on a knowledge of oneself that no one else can have and that is one’s own responsibility.

The final ingredients of this slowly and carefully crafted paradigm are patience and acceptance.

Patience not to force rhythms or forms, to accept the future of things, of flowers, of loves, of bonds. And accept that becoming.

We can put our effort into building these events, but it is necessary to accept that our effort is part of things much bigger than ourselves, and that it is still important and necessary.

When Vanessa talks about her garden and love, she is referring to these elements. With them you do not get the largest garden, nor the greenest, nor the most lush. But you do get a livable garden for everyone, a space of silence in the middle of the noise, a place where you can create necessary stocks, involved in the world and transforming.

Love, heartbreak and earth on the big screens

The cinema has widely collected the relationship between nature and humanity in perpetual friction between the domination of the environment and the pact of life with the natural.

- Towards the Wild is a film directed in 2007 by Sean Penn and based on the homonymous novel by Jon Krakauer that tells the true story of Christopher McCandless, a young American who decided to live isolated in the natural vastness of Alaska. The film reflects the frictions between the urban human being and the irrepressible desire to become natural.

- Atanarjuat, the legend of the swift man , by Zacharias Kunuk, is the first film written, directed and starring entirely in the Inuit language, the language of the Eskimo communities. It tells a millennial story of confrontation between two families in an unlimitedly white and frozen land. Patience, slowness and silence are the common thread of this magnificent film.

- Grizzly man , a documentary directed by Werner Herzog that builds on Timothy Treadwell’s footage of his life among bears. It deals with the limits and possibilities of the relationship with an antagonistic alterity that acts as what it is: bears in their natural state.

- The Embrace of the Serpent , a wonderful film essay directed by Ciro Guerra, narrates the meeting and disagreement between an Amazonian shaman and the last survivor of his tribe and two scientists in search of a plant, a metaphor for the diametrically opposite relationship between one and the other. with nature and with life.